Languages are not born divided. They become divided when history interferes with culture. The story of Urdu, once known as Rekhta, is not merely a linguistic evolution; it is a mirror held up to the subcontinent’s social and political transformations. What began as a shared cultural expression slowly came to be framed as a religious marker, not because the language demanded it, but because history imposed it. To understand this shift is to understand how languages can be shaped—and reshaped—by power, politics, and identity.

Rekhta as a Cultural Meeting Ground

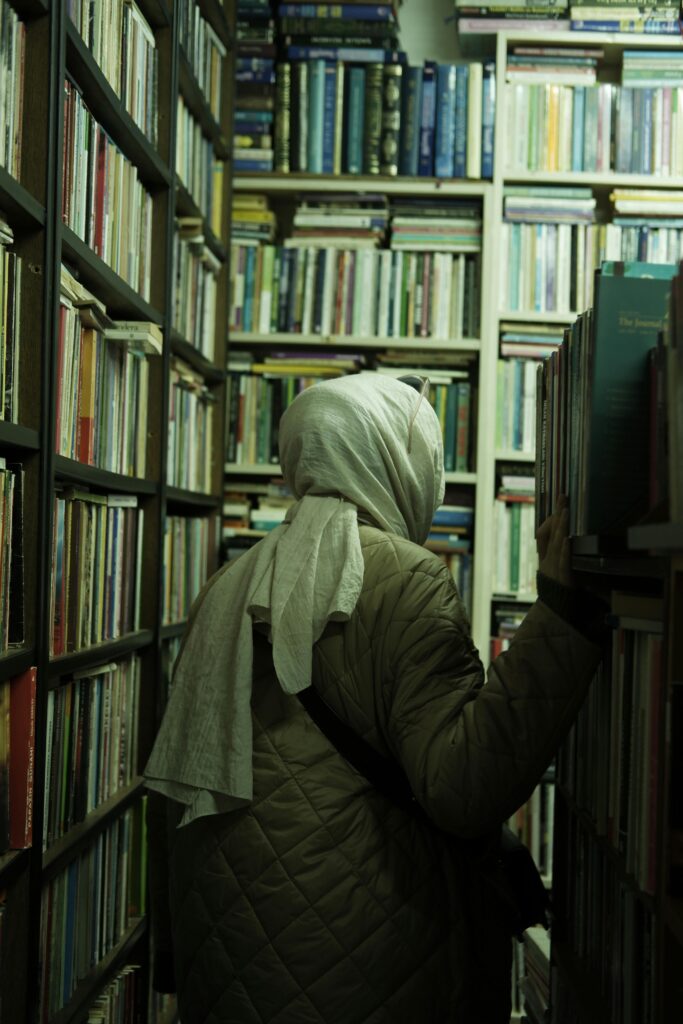

Rekhta emerged as a living, breathing linguistic space rather than a rigidly defined language. It was born in interaction—between Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit, Prakrit, and local dialects spoken across North India. The very word Rekhta means “scattered” or “mixed,” a name that proudly acknowledged hybridity rather than purity. It was not owned by any one community. Poets, mystics, courtiers, soldiers, and traders all contributed to its growth, using it as a bridge between worlds rather than a boundary.

The Role of Persianate Culture in Shaping Rekhta

During the medieval period, Persian functioned as the language of administration and elite culture, but Rekhta developed alongside it as a more intimate mode of expression. While Persian dominated courtly prose, Rekhta found its strength in poetry, music, and everyday speech. Importantly, this linguistic development was cultural, not religious. Hindu and Muslim poets alike wrote in Rekhta, drawing from shared metaphors, seasonal imagery, folklore, and emotional vocabulary rooted in the subcontinent itself.

Poets Before Religious Labels

Early Rekhta poets were rarely concerned with religious ownership of language. Figures like Amir Khusrau moved effortlessly between Persian, Rekhta, and local tongues, reflecting a world where multilingualism was normal rather than exceptional. Later poets such as Wali Deccani played a crucial role in legitimizing Rekhta as a literary language, demonstrating that it could carry emotional and philosophical depth equal to Persian. Their work was read, admired, and imitated across religious lines, reinforcing the idea that language belonged to culture, not creed.

When Rekhta Became Urdu

The transition from Rekhta to Urdu was gradual and organic. The term Urdu itself derives from zaban-e-urdu-e-mu‘alla, meaning the language of the royal camp. This name reflected geography and power structures, not religious identity. Urdu was shaped in military camps and urban centers where people from different regions and backgrounds interacted daily. The language absorbed influences naturally, becoming richer and more expressive precisely because it was shared.

Colonial Intervention and the Reframing of Language

The real fracture began under colonial rule, when language started being categorized, standardized, and politicized. British administrators, eager to classify Indian society into neat compartments, began treating languages as fixed entities rather than fluid practices. Urdu and Hindi, which had long existed on a continuum, were artificially separated through scripts, educational policies, and institutional recognition. What had once been variations within a shared linguistic culture were now presented as opposing languages.

Script as a Tool of Division

One of the most significant turning points was the politicization of script. Nastaliq and Devanagari, once simply writing systems, became symbols of religious affiliation. Urdu, written in Persian script, was increasingly associated with Muslims, while Hindi, in Devanagari, was framed as Hindu. This shift was not linguistic but ideological. Spoken language on the ground remained largely the same, but script became a marker of identity, allowing language to be weaponized in cultural debates.

The Hindi–Urdu Controversy

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw the intensification of the Hindi–Urdu controversy. Language was no longer just a means of expression; it became a political statement. Advocates on both sides began purifying vocabulary, consciously removing shared words to emphasize difference. Sanskritization and Persianization accelerated, pulling the languages further apart. This process transformed cultural variation into ideological opposition, forcing people to choose sides where none had previously existed.

From Cultural Belonging to Religious Ownership

As nationalism gained momentum, language was increasingly tied to religious identity. Urdu was framed as Muslim, Hindi as Hindu, despite centuries of shared literary and cultural heritage. This reframing ignored historical reality in favor of simplified narratives. Poets who had once belonged to everyone were retroactively claimed by specific communities. Language stopped being a shared inheritance and became a badge of belonging—or exclusion.

Partition and the Final Hardening of Boundaries

The Partition of 1947 marked a traumatic rupture not only in geography but in cultural memory. Urdu, which had flourished across North India, became associated primarily with Pakistan and Indian Muslims. Hindi emerged as a national language in India, while Urdu was marginalized institutionally despite its deep roots in the region. What was once a language of cities, streets, and shared emotion was now burdened with political symbolism.

What Was Lost in the Process

In turning Urdu into a religious identifier, much was lost. The language’s plural origins were obscured, its shared history forgotten. Non-Muslim contributions to Urdu literature were minimized, while the everyday linguistic reality of millions who spoke a mixed register was ignored. Language became something to defend rather than something to inhabit. This loss was not merely literary; it was cultural and emotional.

Rekhta as Memory and Possibility

Today, the renewed interest in the term Rekhta represents more than nostalgia. It signals a desire to reclaim a cultural past where language was inclusive rather than divisive. By remembering Rekhta, we remember a time when expression was shaped by lived experience instead of ideological boundaries. It reminds us that languages can belong to people without being owned by identities.

Contemporary Attempts at Reconnection

In recent years, digital platforms, poetry recitations, and cultural initiatives have begun challenging rigid linguistic divisions. Younger generations often navigate Hindi and Urdu without anxiety, switching scripts and vocabularies with ease. This lived multilingualism quietly undermines the idea that language must align with religion. In everyday speech, the old Rekhta spirit survives, even if unnamed.

Language as Culture, Not Boundary

The story of Urdu’s transformation from Rekhta into a religiously marked language teaches an important lesson. Languages are not inherently divisive. They become so when power intervenes. When allowed to grow organically, they reflect shared histories and collective imagination. When constrained by ideology, they lose their capacity to unite.

Rethinking Urdu Beyond Identity Politics

To reclaim Urdu as a cultural language does not require denying its association with Muslim history or literature. It requires expanding the frame to include everyone who shaped it. Urdu’s richness lies precisely in its plurality. Acknowledging this does not weaken identity; it strengthens cultural honesty.

Final Reflections on Language and Belonging

Urdu did not abandon Rekhta; Rekhta was forgotten. Yet memory has a way of resurfacing. Every time a verse moves someone beyond religious labels, every time a word resonates across communities, the original spirit of Rekhta returns. Language, after all, remembers what politics tries to erase. And in remembering, it offers the possibility of repair.